The Rover brand has always been at the heart of Britain’s motor industry, from 1904 to the present day. The products that bear the name Rover are perceived as quintessentially British. Reliable and timeless designs flourishing on innovative engineering and style.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the city of Coventry had become the capital of the British cycle industry. Foremost among many bicycle makers in the city was the Rover Company, which in 1884 had pioneered the modern safety bicycle, which enabled its makers to claim that ‘the Rover Set the Fashion to the World’. The company had been founded in 1877 as a partnership between John Kemp Starley and William Sutton. While Sutton soon pulled out of the business, Starley was to remain at the helm until his death in 1901. As early as 1888, he built an experimental electrically powered tricycle.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the city of Coventry had become the capital of the British cycle industry. Foremost among many bicycle makers in the city was the Rover Company, which in 1884 had pioneered the modern safety bicycle, which enabled its makers to claim that ‘the Rover Set the Fashion to the World’. The company had been founded in 1877 as a partnership between John Kemp Starley and William Sutton. While Sutton soon pulled out of the business, Starley was to remain at the helm until his death in 1901. As early as 1888, he built an experimental electrically powered tricycle.

However the Rover Company only entered into production of self-propelled vehicles in 1903, with the first Rover Imperial motorcycle powered by a conventional petrol engine. In the following year, the first Rover car was introduced – the single cylinder 8 hp model designed by Edmund Lewis which had the first central backbone chassis in the world. A slightly smaller and cheaper 6 hp model of 1905 had a conventional chassis but featured an early example of rack and pinion steering. In the same year, Rover built its first four-cylinder cars, the 10/12 and 16/20 hp models, and in 1907 a 16/20 hp model driven by Earnest Courtis won the Tourist Trophy race in the Isle of Man.

Over the next few years, Rover made a wide variety of cars, including some models with the Knights sleeve-valve engine, but in 1912 two new cars were introduced to replace all the earlier models – a 3.3-litre 18 hp car and the better known 2.3-litre 12hp model, designed by Owen Clegg, and which for many years formed the backbone of the Rover range.

Over the next few years, Rover made a wide variety of cars, including some models with the Knights sleeve-valve engine, but in 1912 two new cars were introduced to replace all the earlier models – a 3.3-litre 18 hp car and the better known 2.3-litre 12hp model, designed by Owen Clegg, and which for many years formed the backbone of the Rover range.

Cycle production continued, and Victor Louis Johnson won a gold medal on a Rover racer in the 1908 Olympic Games, while in 1911 a new 3.5 hp motorcycle was also introduced. Production of two-wheelers continued into the 1920s.

During the First World War, Rover supplied motorcycles to both the British and the Russian Armies, and the company built Maudslay trucks and Sunbeam cars to government orders.

In 1919 a revised 12, which soon became known as the 14, was put back on the market. In the same year, Rover bought a design for a small car produced by Jack Sangster of the Ariel motorcycle company. This became the Rover Eight which was manufactured in a new factory at Tyseley in Birmingham.

The Eight had an air-cooled flat-twin engine, a type of power unit often associated with motorcycles or the contemporary flimsy cycle cars, but the small Rover was well made and sturdy. At one time it sold for as little as £145 and was deservedly popular in the market, until eclipsed by the four-cylinder Austin Seven. In 1924 Rover brought out a complementary four cylinder Nine, and began to move their products up-market, away from direct competition with the mass produced Austins and Morrises. In the same year, the 14/45 was launched – a technically interesting car with an overhead camshaft engine for which Rover for the first time was awarded the Dewar trophy, but a heavy and underpowered car, later fitted with a more powerful engine as the 16/50.

The next few years were difficult for the company. In 1928 the Nine was replaced by the somewhat undistinguished 10/25 which in various forms survived until 1933, and in the same year Rover introduced its first six cylinder model (apart from a prototype 3.5 litre car of 1923). The 1928 2-litre had an overhead valve engine and sold for £410 in tourer form. The Light Six of 1930 cost even less and used the same engine in a shorter chassis. One of these cars, with fabric covered bodywork, entered the history books by beating the famous Blue Train in a race across France. A longer chassis car with a 2.5 litre six cylinder engine of 1930 was christened the Meteor.

In 1931, Rover planned a complete departure from their existing range, with the rear engined Scarab – a small car designed to sell at £85. A prototype was displayed at the London Motor Show but the car did not go to into production. More significant for the future was another show debutante, the 1.4 litre Pilot with a fashionable small six cylinder engine and a freewheel in the transmission.

The Rover Company came under new management in 1933, with the Wilks brothers taking charge – Spencer as managing director, Maurice in charge of engineering and design. Between them they formulated a new product philosophy, that within a few years would make Rover “One of Britain’s Fine Cars”, with a discreet and understated image of typically British quality. For 1934 they introduced new 10 and 12 hp four cylinder models, while the six-cylinder 14 was developed from the old Pilot. It was later followed by similar 16 and 20 hp models, which gave Rover extensive market coverage. Between 1933 and 1939, annual production increased from 5,000 to 11,000 cars, and net profits soared from £7,500 to £200,000.

From 1936 onwards, Rover participated in the government’s shadow factory scheme, building new factories at Acocks Green in Birmingham and at Solihull. With extensive war damage to the original Coventry factory, after 1945 Solihull became the main production site. During the war the company built aero engines and contributed to the early development of Sir Frank Whittle’s jet engine before this project was turned over to Rolls-Royce.

The early post-war range consisted of the 10, 12, 14 and 16 hp models, in saloon or sports saloon form, but in early 1948 Rover brought out their first proper post-war cars – a four cylinder 1.6-litre 60 and the 2.1-litre six cylinder 75, with all new engines featuring overhead inlet and side exhaust valves, in a new chassis with independent front suspension and hydro-mechanical brakes. These cars were known as the P3 models. Rover built another experimental small car, the 700cc two-seater M1, and in 1948 also brought out the Land Rover, with the engine from the 60 saloon, 4×4 and fitted with utility bodywork.

The early post-war range consisted of the 10, 12, 14 and 16 hp models, in saloon or sports saloon form, but in early 1948 Rover brought out their first proper post-war cars – a four cylinder 1.6-litre 60 and the 2.1-litre six cylinder 75, with all new engines featuring overhead inlet and side exhaust valves, in a new chassis with independent front suspension and hydro-mechanical brakes. These cars were known as the P3 models. Rover built another experimental small car, the 700cc two-seater M1, and in 1948 also brought out the Land Rover, with the engine from the 60 saloon, 4×4 and fitted with utility bodywork.

At the 1949 Motor Show, Rover showed the new P4 model, at first only available in 75 form with the six cylinder engine. This had an all new body with full width styling in the American idiom, and for the first few years a very un-Rover like radiator grille with a centrally mounted fog lamp which earned this model its “Cyclops” nickname. It was later succeeded by a version of the original Rover grille, and the P4 range went on to become a much loved car, best known affectionately as the “Auntie” Rover, with a dignified and very British presence. When the P4 range finally bowed out in 1964, more than 130,000 of these cars had been built.

At the 1949 Motor Show, Rover showed the new P4 model, at first only available in 75 form with the six cylinder engine. This had an all new body with full width styling in the American idiom, and for the first few years a very un-Rover like radiator grille with a centrally mounted fog lamp which earned this model its “Cyclops” nickname. It was later succeeded by a version of the original Rover grille, and the P4 range went on to become a much loved car, best known affectionately as the “Auntie” Rover, with a dignified and very British presence. When the P4 range finally bowed out in 1964, more than 130,000 of these cars had been built.

A P4 was the basis for the extraordinary JET 1 of 1950, the world’s first gas turbine engined car, inspired by Rover’s wartime involvement with the jet engine. This car earned Rover the Dewar trophy for the second time and was driven at speeds over 150 mph. Over the next few years Rover built several experimental gas turbine cars, including the T3 of 1956, a four-wheel drive coupe with a glass fibre body, the T4 of 1962 with front-wheel drive based on the as yet unannounced 2000 model, and finally, in co-operation with BRM, a racing car which competed in the Le Mans

24 hour race in 1963 and 1965, finishing tenth in the latter year at an average speed of over 100 mph. Subsequently however the company gave up turbine development as the technology was not yet suitable for production cars.

A major step ahead for Rover came with the P5 model of 1958, a large luxury saloon with a 3-litre version of Rover’s six-cylinder engine. It was the first Rover car with unitary bodywork, styled by David Bache. This model combined elegance with dignity, and had a traditionally well-appointed interior. Later developments of the P5 included the more rakish coupe with a lowered roof line, and the 3.5 litre V8 model of 1967 which for the first time used the all aluminium V8 engine to a design bought from the American Buick company. The 3- and 3.5-litre models became favourites for transport of dignitaries, including British Prime Ministers from Harold Wilson to Margaret Thatcher, and HM The Queen used these cars for her private motoring.

A major step ahead for Rover came with the P5 model of 1958, a large luxury saloon with a 3-litre version of Rover’s six-cylinder engine. It was the first Rover car with unitary bodywork, styled by David Bache. This model combined elegance with dignity, and had a traditionally well-appointed interior. Later developments of the P5 included the more rakish coupe with a lowered roof line, and the 3.5 litre V8 model of 1967 which for the first time used the all aluminium V8 engine to a design bought from the American Buick company. The 3- and 3.5-litre models became favourites for transport of dignitaries, including British Prime Ministers from Harold Wilson to Margaret Thatcher, and HM The Queen used these cars for her private motoring.

In 1963, Rover entered a new market sector with the P6 2000 model. This was a compact and sporting saloon which started the trend to the so called “executive” cars. It had an all-new overhead camshaft four-cylinder engine, an all disc brake system, and a de Dion rear axle. It was the first British car to be fitted exclusively with radial tyres.

Its advanced engineering and styling, coupled with traditional Rover values, earned it the accolade of Car of the Year, in the first year that this international award was made. Later on, the P6 range was extended with the V8 engined 3500 model, which put Rover on the map as a high-performance car. The last derivatives of the P6 were made in 1977, by which time the range had become the best-selling Rover ever with a total production in excess of 325,000.

Its advanced engineering and styling, coupled with traditional Rover values, earned it the accolade of Car of the Year, in the first year that this international award was made. Later on, the P6 range was extended with the V8 engined 3500 model, which put Rover on the map as a high-performance car. The last derivatives of the P6 were made in 1977, by which time the range had become the best-selling Rover ever with a total production in excess of 325,000.

The steady contraction of Britain’s motor industry in the post-war period would not leave Rover untouched. In 1965, Rover bought the small Alvis company of Coventry, maker of hand built luxury cars as well as military vehicles, and in the following year Rover was in turn bought by the expanding Lancashire based truck maker Leyland who already owned Standard Triumph. Then in 1968, the grand alliance of Britain’s motor industry was created when the Leyland group merged with Britain’s largest maker of popular cars, BMC, whose roster included Austin, Morris, MG and other makes, and which had previously allied itself with the Jaguar company. Within the Leyland hierarchy, Rover was eventually merged with Triumph (and, for a time, Jaguar) as a maker of upmarket specialist cars.

The P5 model was discontinued in 1973 without a successor – an even larger and more luxurious P8 prototype remained stillborn, reputedly as it was thought to be too close competition for the Jaguar XJ6. Similarly, the mid-engined P6BS sports car did not go into production, but an important newcomer was the first Range Rover of 1970 with which Land Rover expanded their range of four-wheel drive vehicles into the luxury sector.

The next new Rover car was the SD1 of 1976, which like the P6 before it took the Car of the Year title. Initially available only with the V8 engine as the 3500 model, the range was subsequently widened with four and six cylinder versions, as well as Rover’s first diesel engined car. The engineering of the SD1 was less adventurous than its P6 predecessor but its sleek five-door fastback body gave it a unique market position in the executive class. The SD1 became a successful saloon racing car and with this car, Rover won their second TT race only 76 years after the first. A fuel injection engine was fitted to the Vitesse version, which was the fastest Rover production car.

The next new Rover car was the SD1 of 1976, which like the P6 before it took the Car of the Year title. Initially available only with the V8 engine as the 3500 model, the range was subsequently widened with four and six cylinder versions, as well as Rover’s first diesel engined car. The engineering of the SD1 was less adventurous than its P6 predecessor but its sleek five-door fastback body gave it a unique market position in the executive class. The SD1 became a successful saloon racing car and with this car, Rover won their second TT race only 76 years after the first. A fuel injection engine was fitted to the Vitesse version, which was the fastest Rover production car.

Meanwhile, the parent company British Leyland had encountered financial difficulties, which in 1975 led to the effective nationalisation of the company. A programme of drastic restructuring was initiated by Michael Edwardes, who became chairman in 1977.

He initiated the link with the Japanese Honda Company with selected Honda cars being built under licence – an example was the first Rover small car for many years, the first 200 series of 1984, which was also the first front-wheel drive Rover car. A programme of joint development was then started for a new executive car; project XX, which was introduced as the first Rover 800 in 1986.

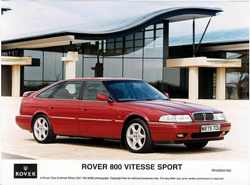

This was also a front-wheel drive car, fitted either with a Honda V6 engine or Rover’s own new 16 valve 2 litre four cylinder engine, originally available only as a four door saloon but later joined by a five door hatchback which was offered as a high performance Vitesse model. In the same year that the 800 was introduced, Graham Day was appointed as chairman of BL.

He quickly renamed the company Rover Group and began a programme of moving the company and its products up-market, away from the mass market. He was also charged with completing a privatisation programme, which so far had seen many BL subsidiaries (including Jaguar) being sold. In 1988, this was finally accomplished with the sale of Rover Group to British Aerospace.

It was part of Day’s philosophy that henceforth, all new saloon models should be called Rover, with the MG badge being reserved for new sports cars. There were also further joint product developments with Honda, including the new 200 series of 1989, which was fitted with the new 1.4 litre K series engine – a revolutionary design, which earned Rover the Dewar trophy for the third time.

The original five door 200 saloon was soon followed by a host of derivatives, including the booted four door 400 of 1990, while in the same year the K Series engine was also fitted in the Rover Metro – a much developed version of the corporate best selling small car which later became the 100 series.

A return to more traditional brand values was signalled in 1992 when a new 800, for the first time since the demise of the P5 almost 20 years before, featured a version of the classic Rover radiator grille, and a luxurious coupe version was added to the range. In 1993, the elegant 600 was introduced, a saloon which was manufactured together with the 800 models in a new facility at Cowley near Oxford, while production of the smaller Rover models was concentrated in the Longbridge factory in Birmingham.

A return to more traditional brand values was signalled in 1992 when a new 800, for the first time since the demise of the P5 almost 20 years before, featured a version of the classic Rover radiator grille, and a luxurious coupe version was added to the range. In 1993, the elegant 600 was introduced, a saloon which was manufactured together with the 800 models in a new facility at Cowley near Oxford, while production of the smaller Rover models was concentrated in the Longbridge factory in Birmingham.

After six years in the ownership by British Aerospace, in early 1994 the Rover Group was taken over by German carmaker BMW. Under the new owner, Rover could begin to fulfil its potential, and 1995 saw two important new models. First the 400, a medium-sized car available in saloon and five door versions, and then at the end of the year, the new 200, a three or five door hatchback with a youthful appeal. Both featured versions of the well-established K Series engine, and also Rover’s new much acclaimed L Series diesel engine. In 1996, the ageing Honda V6 engine in the 800 series was replaced by Rover’s own new KV6 2.5-litre engine, pointing the way to future developments for the brand. The development of a new, classic but modern Rover was being developed to be everything that a forward looking Rover should be, and was being prepared for launch in 1998.

The Rover 75 Saloon was introduced under the objective of creating ‘the best front-wheel drive car in the world’. The elegantly proportioned Rover inspired the media and a variety of international awards followed.

The Rover 75 Saloon was introduced under the objective of creating ‘the best front-wheel drive car in the world’. The elegantly proportioned Rover inspired the media and a variety of international awards followed.

On 16 March, BMW Group announced fundamental ‘re-organisation plans’ that split the company apart, despatching Land Rover to Ford. The Phoenix Consortium acquired the Rover Group business, comprising the MG and Rover brands, on 9 May 2000. However, BMW retained ownership of the Rover name and licensed the use of it to the new company. For the first time in many years the company found itself independent, British owned and debt free. The future would focus strongly on the MG and Rover brands, under the MG Rover Group operation, free to develop without constraint of partnership or ownership restrictions.

The Rover 75 Tourer followed soon after in the May and extended the versatility of the Rover portfolio. At the Geneva Motor Show, a long wheelbase version of the 75 was announced, with the Rover TCV ‘stealing the show’. Rover’s design direction illustrated a new journey into a modern era.

Despite being face lifted in 1999, the 25 and 45 were middle aged. MG versions of the existing model range were speedily devised to maintain their appeal in an increasingly competitive market. However, this was ‘window dressing’ for the main event – a new car to replace the 45/ZS. The plan was to have the new car, based on the running gear of the 75, on the market for 2004.

However, disaster struck in 2003. First, TWR, who were to complete the productionisation, went bust. then soon after the announcement of a potential partnership with China Brilliance (DBIH), CBIH pulled out (after paying MGR around £50m) leaving MGR with little more than a few million extra in the bank and a few more vital months lost.

Negative publicity surrounding the Phoenix Four pension fund had an effect on public perception of the company. After a short period of tentative sales growth, and a serious reduction of trading losses in 2003, the company’s fortunes turned. With sales falling, the future had started to look bleak. The launch of the City Rover and the face lifted versions of the 25, 45 and 75 and the magnificent Rover V8 didn’t have any effect.

Salvation seemed to be on hand in June 2004 when MGR announced that it was in talks with the Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation (SAIC) about future collaboration. In the months leading up to the planned signing of the deal, MG Rover executives sold the intellectual Property Rights of the 25, 75, TF and K-Series engines in two tranches for a reported figure of around £67m. Following an emergency meeting during the Easter break of 2005, it became apparent that SAIC was unhappy with the status of the 45/ZS replacement programme, and were becoming increasingly alarmed at the rate MG Rover was now losing money.

The deal floundered and car production was halted on April 7, 2005, with the administrators, PricewaterhouseCoopers, moving in the following day. Despite the workers’ best efforts, the dream was over; MG Rover production as we knew it had ended.

Following the acquisition of Jaguar and Land Rover by TATA in 2008, BMW sold the Rover name to TATA. Only time will tell if we are to see a new car launched wearing the famous Viking prow in the future.

(Adapted from an MG Rover Press Release).